[In this post I will refer to ‘horizons’. This concept is not a new idea but describes a viewpoint, a perspective looking forward. Mountain ranges can be hard to separate one from the other, so the concept is of a blurring of the future so that there only appears to be one ‘horizon’ or the separation of the ranges so that there are multiple horizons. I owe the clarity of this to Andrew Perriman, though our view of what the horizons are differs. I am just too much of a ‘conversion of Constantine was ever so bad’ kind of person to go with Christendom as a fulfilment of hope!]

If we say that ‘Jews believed’ or the ‘Jewish hope was…’ we do have to realise that the Jewish faith was not monolithic, so we have to make allowances for divergent beliefs. We see this with the hope for a Messiah. That could vary from a Messiah who would be royal, or a Messiah who would be priestly, or two Messiahs, or none! Somewhat varied. However, it is certainly not wrong to suggest that widespread among Jews was the hope for an intervention of God (whether through the agency of Messiah or not) that would put all things right and fulfil the hopes of Israel, thus restoring the kingdom to Israel.

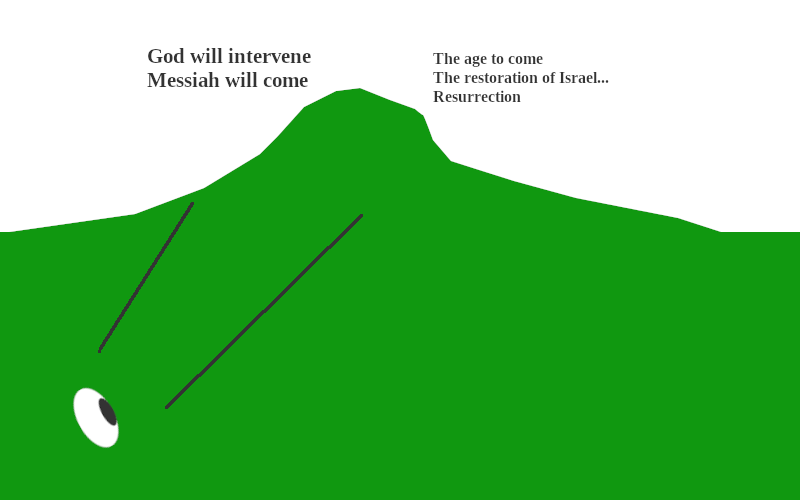

This age would end and the age to come would be present (the word often translated ‘eternity’ is simply the word for ‘age’, eternal life being life of ‘the age to come’; the shock of the New Testament was that the life of the age to come was being offered in the here and now). There might be a process involved in this coming age being present but there would be a definite before and after. We can represent this as a ‘one horizon’ view:

The hope was simple – a one horizon view – that God would intervene. It might take place over a period of time but the result would be the end of this present (evil) age, the restoration of Israel, the rule of God over the nations, the kingdom of God would have arrived. Into that there was a predominant view that God would resurrect the righteous to benefit from the new era. Finally, it should be noted that all of the above would occur within this world, the idea of this being a celestial experience in heaven was not held.

There were expectations and hopes for the intervention of God at various times in history and certainly there was a lively expectation expressed in the opening pages of the New Testament. John was asked directly if he was the Messiah. Jesus prophesied that in the years after the crucifixion there would be Messianic figures who would arise. The hopes were alive for the intervention of God for the overriding view was that in spite of a return to the land they were not free; Israel was an occupied land, the people were far from being ‘the head not the tail’. A return to the land did not signify the end of the Exile.

In 587 Jerusalem was destroyed along with the temple by Babylon. The prophets spoke of the hope for the end of exile, and indeed after a span of time some did return, a temple was built, but it was inferior to the one that had been destroyed. Later the land became subservient to the Greek then the Roman empire. The question continued as to when God would intervene.

The two disciples on the way to Emmaus verbalised how their hope had been in Jesus as being the one who would bring about the restoration, they were living (as were the other disciples) with that one horizon viewpoint:

The things about Jesus of Nazareth, who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, and how our chief priests and leaders handed him over to be condemned to death and crucified him. But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel (Lk. 24:19-21).

Within the Jewish world there were those who spoke of the exile as continuing, This perspective is explicitly stated in the inter-testamental work of Baruch:

So to this day there have clung to us the calamities and the curse which the Lord declared through his servant Moses (1:20)

and again

See, we are today in our exile where you have scattered us, to be reproached and cursed and punished for all the iniquities of our ancestors, who forsook the Lord our God (3:8).

So although there was a stream that rejoiced that there had been a return to the land after Babylon the verdict of history was of the Exile, at least in part, continuing. The same ‘exile is continuing’ is framed in Matthew’s Gospel. Jesus will forgive his people (Jews) their sins (the reason for the Exile / oppression) and in his person God will be with them, for his name was to be Emmanuel.

The hope then we can express as looking to the future and somewhere on the horizon there would come ‘the restoration of all things’.

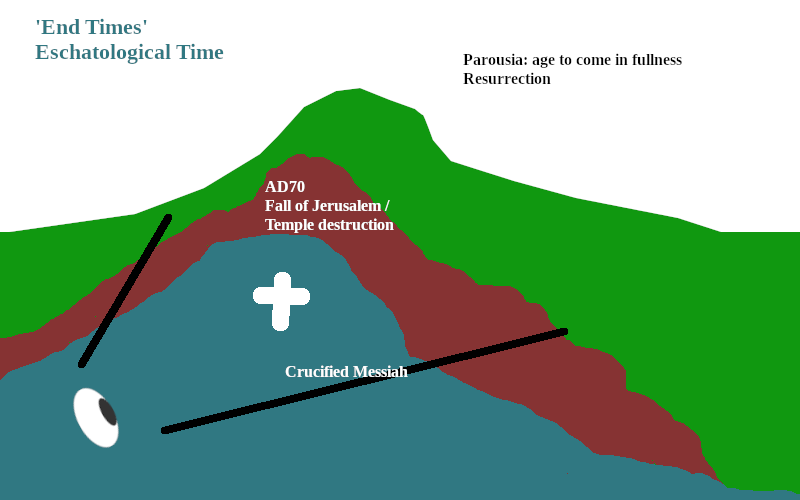

The transformation of the one horizon perspective

The coming of Jesus greatly changed the ‘one horizon’ view. What was not embraced was the death of Messiah, for Messiah was to conquer all the enemies of God’s people and purpose, not be conquered by them. The crucifixion was not visible as part of Messiah’s journey to (for example) Peter, who saw Jesus as the Messiah, ‘the Christ of God’. After proclaiming that Jesus was the Christ he then rebuked Jesus for indicating that death in Jerusalem lay ahead. Only a failed (and hence a false) Messiah could be sentenced to death. There was no concept within the one horizon perspective for the crucifixion, indeed it could not be so as anyone who was hung on a tree was considered ‘cursed’, and Messiah certainly could not be cursed (Deut. 21:23; Gal. 3:13).

The death of Jesus at Easter / Passover was not foreseen, indeed it was resisted, and when it took place it destroyed their hopes. The other side of the resurrection, the death on the cross was seen as the defeat of all enemies, even the ultimate enemy, death itself, and this defeat of death was essential as the original story had been that death entered the world through the sin of humanity.

This new horizon gave sight to a God who intervenes not to destroy the perceived enemies of Israel but the spiritual forces that captivated Israel (and the nations). This immediately shifts our understanding of the promises of God within the Old Testament narrative. The resurrection taking place in a garden surrounded by death speaks loudly (as does the identification of Jesus by Mary as ‘the Gardener’) that the crucifixion was restoring the original commission, the possibility now of working to bring creation to a place of restoration was present.

We might take the various events from the cross, the resurrection, the ascension and pentecost as one event, indeed so they are as they all flow together, but if I separate out pentecost we really have a re-enacting of the creation of humanity. Taken from the dust, the life of God being breathed into them, so that they, as community, might be a new humanity. We can take pentecost as a new horizon or part of the same horizon.

From the breathing into those first disciples a movement is released with the last word of Acts being ‘unhindered’, we understand a movement that was always anticipated to continue, not a movement that would fade out. The breath is a new creation, but the mandate from that first creation is picked up. Subduing the earth and multiplying. The growth and expansion is clearly noted throughout Acts. We read phrases such as:

- Added to their number (Acts 2:47).

- But many of those who heard the word believed (Acts 4:4).

- A great number of people would also gather from the towns around Jerusalem (Acts 5:16).

- You have filled Jerusalem with your teaching (Acts 5:28).

- The word of God continued to spread; the number of the disciples increased greatly in Jerusalem, and a great many of the priests became obedient to the faith (Acts 6:7).

- Samaria had accepted the word of God (Acts 8:14).

- Proclaiming the good news to many villages of the Samaritans (Acts 8:25).

- He proclaimed the good news to all the town (Acts 8:40).

- Meanwhile the church throughout Judea, Galilee, and Samaria had peace and was built up. Living in the fear of the Lord and in the comfort of the Holy Spirit, it increased in numbers. (Acts 9:31).

- This became known throughout Joppa, and many believed in the Lord (Acts 9:42).

- But the word of God continued to advance and gain adherents (Acts 12:24).

- Thus the word of the Lord spread throughout the region (Acts 13:49).

- This continued for two years, so that all the residents of Asia, both Jews and Greeks, heard the word of the Lord (Acts 19:10).

- So the word of the Lord grew mightily and prevailed (Acts 19:20).

- Without hindrance (Acts 28:31).

Multiply and fill the earth, a new humanity with the breath of God living among the ‘animals’, both domestic and wild (beasts). From the creation narratives the nations were understood to be like animals and some of them – those who sought to oppress others – were described as beasts. This multiplication was taking place throughout all the nations of the earth, the earth was being subdued, not through some top-down force of will, but through a people who were understanding that they were to love, nurture and inspire a bending of powers to heaven’s ways.

A transformation of understanding of that one horizon expectation. The cross was necessary to defeat the powers, to enable the release of those carrying the breath of the Spirit to partner together, and with heaven, in ‘subduing the earth’ and ‘multiplying’.

The ultimate horizon

There are two horizons beyond the pages of Scripture: one we might call the ultimate one – the parousia; the visible appearing of Jesus (‘he will appear a second time’ Heb. 9:28).

This of course is what most people mean when they talk about eschatology, but they often focus more on a set of events that will take place, with the return of Jesus the appendix to a set of events. It is questionable if a set of events that take place in the so-called end-times are indicated in Scripture. What is pointed to is not a set of events but a final appearing of Jesus that ushers in the ‘new heavens and the new earth’, the time when all things are ‘made new’ (not ‘all new things are made’!), that brings about the fullness of the restoration of all things.

I have written about an end-time horizon, from that first Easter to the breath of God into human clay on the day of Pentecost; and in the preceding paragraphs I have written of an ultimate end-time horizon: the parousia of Jesus. Between that first and final horizons lie one other horizon. It is important to grasp this for without that understanding we are likely to try and make some major extensive words of Jesus concerning Jerusalem’s future fit into some end-time scheme. The words of Jesus (as recorded in Matt. 24; Mark 13 and Luke 21) are addressing a future that unfolds after the majority of Scripture has been written and some 40 years after Jesus died. It is important to note those events.

AD70: the fall of Jerusalem

Prior to that final horizon breaking in on us there is an event that was ultra-traumatic, an event that certainly was not anticipated and certainly would never have been seen as a God-intervention. The concept of the total destruction of Jerusalem could only be understood as a major setback and a killer-blow to hope. The war with Rome (66-70AD) occurs after the majority of the writings that we now have that we term the New Testament (I date Revelation, at least in the form that we have, as being later than 70AD and is addressing a different context, the fall of Imperial power), so we do not have details of that war within the pages of the New Testament but we do have clear predictions concerning it.

When we talk of the ‘end of the age’ we should not think primarily of the destruction of everything related to this world, but of such a transition from one era to the next that the world as was known would come to an end. Such was the effect of the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple in AD70. It felt like the end of the age, for it was the end of the age, the end of the ordering of the world as it was – it marked a significant before and after.

If we do not take note that many of the Scriptures relate to the period between the first Easter event and the fall of Jerusalem (40 years, the suggested length of a generation) we will universalise those Scriptures and miss the narrative that is being unfolded. Conversely, if we allow those Scriptures to speak into their context we will follow the trajectory of the narrative and allow all Scripture that was not written to us to be powerfully available as being for us.

Jesus in his prophecy concerning the fall of Jerusalem states that this will take place within a generation,

Truly I tell you, this generation will not pass away until all things have taken place (Lk. 21:32).

Truly I tell you, this generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place (Matt. 24:34).

And in Acts as the proclamation is made to those within Jerusalem we find that there are texts that fit right into how the listeners are to respond. They are to save themselves from ‘this generation’ (Acts 2:40) otherwise they will be ‘will be utterly rooted out of the people’ (Acts 3:23). It is this context that we have to place the declaration that,

There is salvation in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given among mortals by which we must be saved (Acts 4:12).

Yes it has universal application, but the context is to Jews who could claim Abraham as their ‘father’, the one who was given the covenant of circumcision in which they were included. Something had shifted; Messiah had come; salvation was now in Messiah’s name.

The fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple was devastating. In the closing days of the resistance the Romans were crucifying up to 500 at a time within sight of the walls; cannibalism was taking place inside the city; the corpses of those who died were being thrown over the walls into the valleys outside (one of which was the valley known as Gehenna – often translated as ‘hell’). Jesus warned of what was to come, which Luke records in straightforward language that Gentile converts who were not so accustomed to the language of Daniel (‘the abomination that causes desolation’) could understand:

When you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies, then know that its desolation has come near (Lk. 21:20).

A generation after that first Easter there was truly the end of an age. Time was called, but as we read in Acts, the proclamation of the kingdom of God and the teachings about Jesus continued unhindered.