We have stopped in a number of places to see, pray and receive, but yesterday was the most focused of days. We had been given a word about taking time at a border for there we would receive for the ongoing journey and receive some kind of partnership with angels. Borders: Spain to France; France to Germany; Germany to Switzerland; Switzerland to Italy; and of course ‘smaller’ borders between provinces and the sea border between Italy mainland and Sicily is yet to come. So which border?

Borders are important and I am not too fussed what we make of ‘angels, principalities and powers’ but at the minimum they speak of authorities that either shape the context or are shaped by the context. I am not convinced we have to be correct in our theology but it sure helps to do our best to align with whatever the Scriptures are describing. Jacob encountered angels at a border both when leaving his family on the way to Laban’s household and also when he returned. Paul described how God had set boundaries for the peoples (and kairos times) so that they might seek after / stumble and find God. Hence boundaries are important and the crossing of them is what transgression speaks of and is a sure way to remove the environment where people can seek after and find God. (Of course there is much more to it than that, but to ignore the issue of boundaries and land we will miss a whole aspect of the release of ‘good news’.) Paul and Luke seemed to have used the Roman names for territory and Paul’s journeys were led by the Spirit but within defined geographical settings.

So which border?

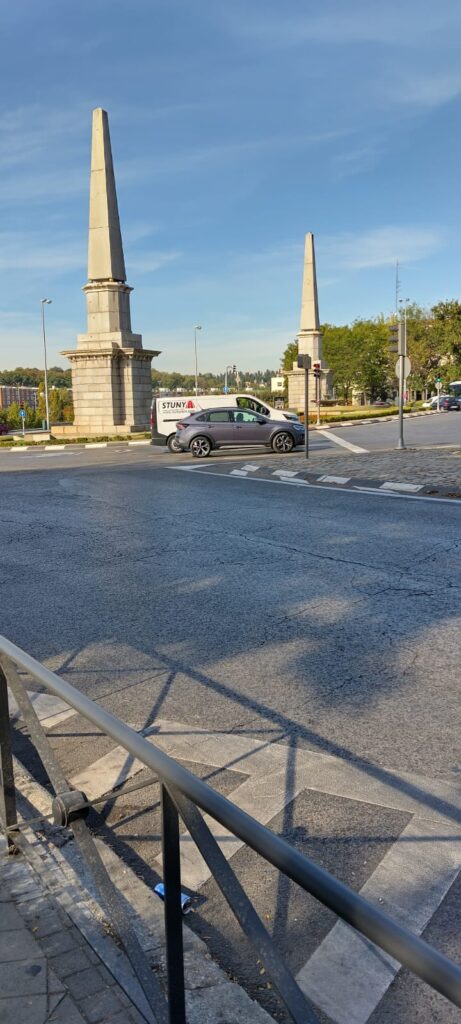

We were convinced that the border we needed to give attention to was an ancient border – the northern border of the kingdom of the two Sicilies. To the north was the papal lands and to the south the kingdom of the two Sicilies.

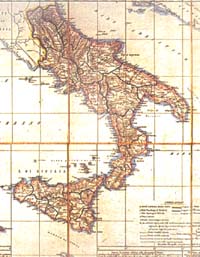

It was the “Kingdom” par excellence. Its territory was delineated since the very first years of its creation under Roger II of Altavilla and remained unchanged along the centuries until its fall in 1861: its northern boundary followed a line that stretched out from Civitella del Tronto (south of Ascoli) to Gaeta and touched Leonessa, L’Aquila (north of Pontecorvo) and then continued south to the Tyrrhenian Sea; its southern boundary was the sea itself, including Sicily.

https://realcasadiborbone.it/en/history/an-ancient-and-glorious-kingdom/

For around 730 years this territory holds that boundary. And of course in the history there are the inevitable clashes and alignments between so-called secular powers and the religious powers exercised by the pope. The uneasy history! The annexation of the two kingdoms was the effective start of the unification of Italy under Garibaldi (1860 onwards).

The map to the left is that of the ancient division, and we have been staying approximately 2 kilometres north of the line on the western coast. Noe Limiñana laid an ancient map over the current map of the area and came up with the border as being marked by a river – the Rio Claro. This is where we focused yesterday and (of course could be subjective) the witness in our spirit when we stood on the bridge over the river was very strong. The ancient border! We ‘felt’ (oh yes possibly simply subjective) that there was a difference one side to the other… angels going with us? I am sure there will be though neither of us had specific dreams last night – something that would be expected.

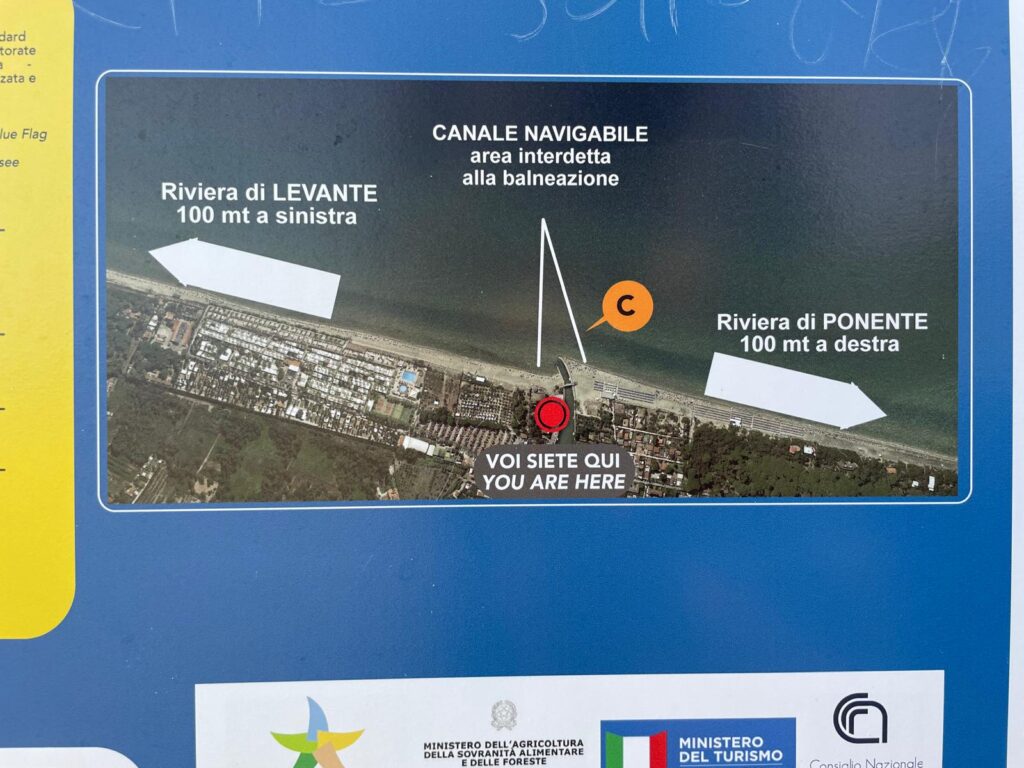

Coming off the bridge we smiled when we saw this sign on the sea front indicating the flow of water divides at that point. One direction back and one direction toward our destination:

As we travel today our prayer and speech will be concerning the open arms of God to one and all. Borders over coming years might change… but let them fit with what will facilitate a ‘finding of God’.

Coincidentally(?) a camp site on the border is named ‘Anastasia’, after the goddess. It was Paul’s proclamation of ‘Jesus and the resurrection (ἀνάστασις)’ that was central and misunderstood as two deities: a new one (Jesus) and an ancient Greek one (Anastasia). A good reminder – Jesus cannot be proclaimed without the resurrection… and if proclaimed then everything has changed and we have to live from that perspective, the perspective of the new creation.

Tonight we should be right down in the south ready to get a ferry tomorrow to Sicily. For sure angels go with us as they do with all who seek to partner with God.